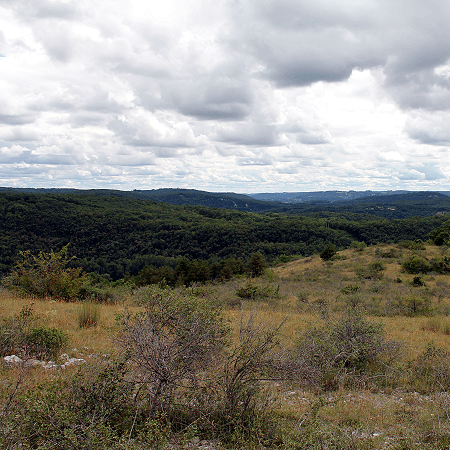

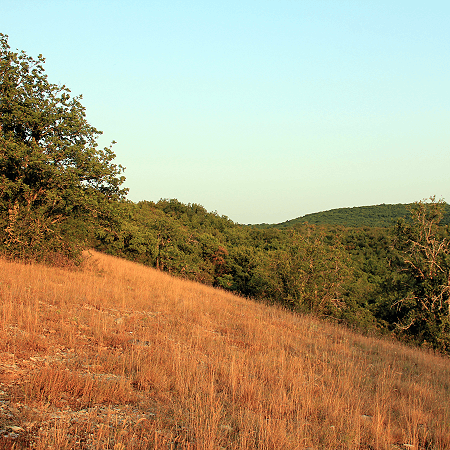

Introduction to the landscape

As this area is easily accessible from Terrasson it allows for in depth exploration of the landscape through one of the many hiking trails. The landscape is shaped by the interaction of the underlying geology, topography, biology, contemporary culture and deep historic factors. Celtic people build their ‘oppodia’ (large earthworks), castles like that of Montmège were later build on them. The Roman empire left its traces in roads and villas with mosaic floors as displayed in the Patrimony House of Terrasson.

![]()

The Merovigian and Caroligian ages left fewer marks as they lacked the political organisation and largely build in wood, though some sarcophagi can be seen of Place de Genouillac in Terrasson. And the VIth century hermits: Amand, Cyprien and Sour left their marks by founding monasteries. But a lot of what is visible in the landscape today finds its origins in the XIIth century renaissance.

From the XIth century onward new hamlets and the extension of agricultural land began changing the countryside. This population growth was accompanied by large social changes, were in the Xth century slaves were still common, the practice had practically disappeared in the XIth. The emergence of feudal system replaced the legal inferiority of the non-free with the economic dependence of the peasant.

The peasant gained an interest in the management of ‘his farm’ as he could transfer improvements to his children (though the land was not yet legally his to sell). Relative autonomy and autarky (ability to survive and function without external assistance) shaped a ‘peasant mindset’, still shaping to landscape today (see below).

Though; ‘what the lord gives with the one hand, he takes with the other’. No longer ‘hands-on’, the feudal lordship starts taxation through the exploitation of banalities; the banal press, the market hall and the banal oven…etc., that can still be found scattering the landscape. Water mills start multiplying on the watercourses milling flour, oil, tannin, malt, powering forges, crushing fibres for textile or beating iron.

Because these activities are easily taxable, they increase the income of the lordship, opening new social perspectives to the aristocracy, as well as new investment opportunities ‘for the benefit of all’. It contributes to the resurrection of a monetary economy, neglected in the times of village self-sufficiency since the fall of the Roman Empire.

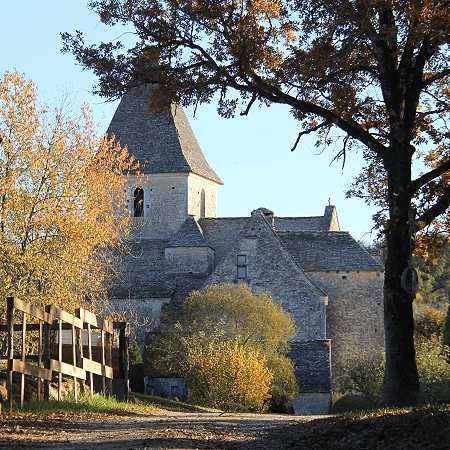

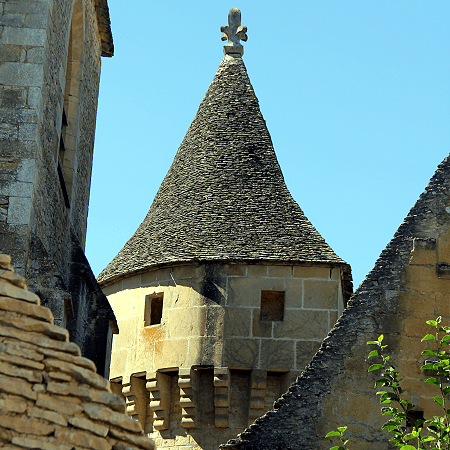

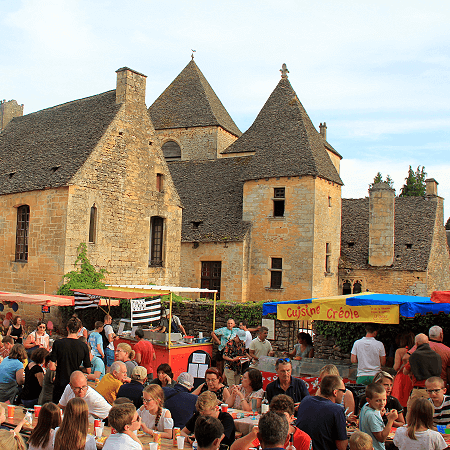

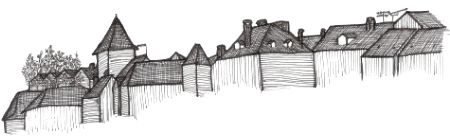

In Aquitaine, castles build in local natural stone become the focal point of a lordships: Prestige, profit and protection go hand in hand, as dungeons, pigeon towers, bridges and large stone enclosures circling the ‘bourgs’ are constructed. Far from the old cities, ‘bourgs’ (big villages) are created at the foot of a castle or monastery, attracting and protecting activities that could further enrich the lordship. However, the ‘free people’ of the bourg (the bourgeois), taking advantage of the rivalries between the local lords and authorities, had to be given various franchises to encourage their settlement.

The same period also sees the growth of pilgrimages to Rome (the tomb of St. Peter), Compostella (the tomb of St. James) and Jerusalem (the Holy land). The ideal lord, the knight of chivalry, goes on a pilgrimage (or crusade metaphorical or for real) for his eternal salvation.

The orders of chivalry; the order of the Temple and the order of St. John of Jerusalem (better know as Knights Hospitalier or Hospitallers for short) emerge in the aftermath of the first crusade. Their support networks of commanderies become effective land exploitations and important actors of economic development. Condat-sur-Vézère was the seat of the principal commanderie of the Hospitallers which had authority over the network of commanderies of the Périgord.

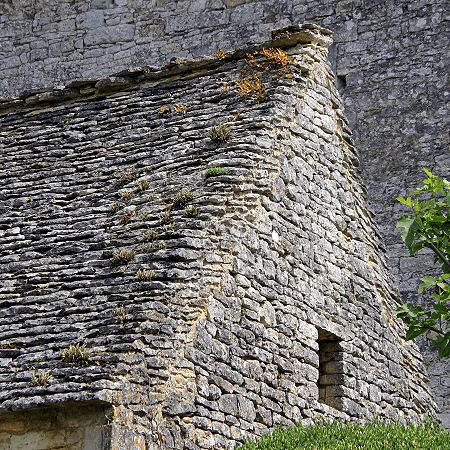

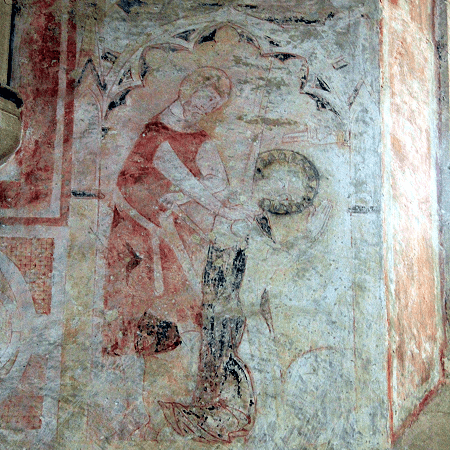

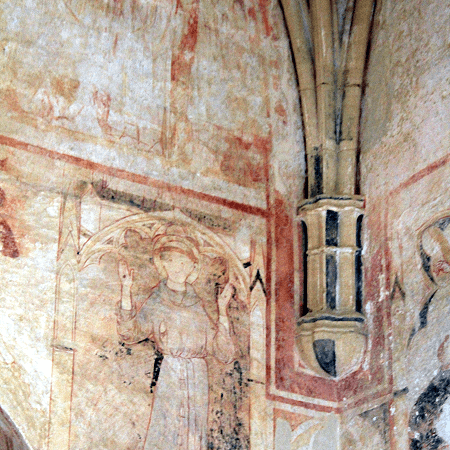

Fortress-like churches in the Romanesque style appear with their massive walls, round arches, small windows and arch framed portals. Exterior decoration of Romanesque churches is relatively simple, inside walls often adorned with frescoes, but few survived as stucco pealed-off and was removed. The bare natural stone walls, clean lines of the arches and domes resonate with the contemporary mindset.

The Romanesque style is a diverse expression of the vernacular, sometimes divided into regional schools of architecture. The Ecole du Périgord typically has a line of cupolas/domes and often a steeple-wall (Un clocher-mur; vertical flat architectural element constructed at the front containing the main entrance and church bells). The most impressive among the Romanesque churches of Périgord is the abbey church of Saint Amand de Coly.